With the internetty part of SXSW well behind me, it seems like a good time to talk a bit more about the state of our community (if it can be called such a thing) and its origin myths.

It seems as though disillusionment and cynicism are growing within our ranks. Alex Payne does a nice job rounding up some examples. As noted here recently, it’s difficult to separate this sense from the process of growing older (Alex is not much younger than me). Still, I perceive it to be a real shift. I think there are specific reasons for it, and that its arrival was inevitable.

It’s an axiom of internet true-belief that things will get faster. Mostly, this is true. Moore’s Law is habitually misstated, but even when the details are mangled the speaker’s point often remains defensible. Digital technology really does get cheaper in a hurry, and this has real consequences for its reach and impact on our lives. Faith in this ceaseless acceleration reaches its apotheosis in the idea of the Singularity, an long-nascent idea popularized by Ray Kurzweil, which posits that technological change will reach a velocity beyond which meaningful predictions about human society are impossible to make. Many people guess that this will involve mind-uploading, but the point is really just that we won’t be able to anticipate the true nature of the silicon godhead. Kurzweil was at SXSW, but I can assure you that he wasn’t the only person in Austin hoping/expecting that his mind will live forever in a machine or otherwise achieve technological transcendence.

Many find this faith in technological acceleration to be cheering, but it’s got some problems. Perhaps most importantly, it ignores the reality of diminishing marginal utility. Put simply: useful interventions tend to get less useful as you apply more of them to a problem. Digital technology can do a lot of things, and its declining cost means it will do more and more of them. But it’s important to realize that many of the things it could do but didn’t back when it was more expensive weren’t done because they weren’t worth the expense.

My toothbrush has a microprocessor in it; it’s great, and it only cost me $50 or so. It times my brushing and it ramped up the strenuousness of its sonic ministrations when I first began using it. Two decades ago, no such toothbrush was available. Why? There are a number of possible explanations. Perhaps the technology didn’t exist? No, that’s not right, it certainly did. Perhaps the toothbrush makers of the past were less clever than the folks gathered in Austin? No — that seems improbable, or at least egotistical. I think a better explanation is simply that, at the time, the advantages of a microprocessor-enabled toothbrush didn’t justify the expense of building it. The expense diminished, so now we have them. But it’s the costs that fell; the utility has remained static, and meager. This is strictly long-tail stuff.

Put another way: the most urgent uses for a technology will be addressed first. That’s the beauty of markets. But a consequence is that, during a given technological milieu, engineers will generally find themselves working on tasks that increasingly seem trivial.

I don’t think developers should be discouraged by this, but I suspect that many of them will be. That’s too bad. There’s no shame in doing honest work for honest pay. I’ve argued before that software development is a trade comparable to carpentry. I still think that’s about right. Building someone a home may not be “innovative”, but it’s a necessary and important thing. There will always be meaningful work that needs to be done, and, if you pursue work that is especially difficult or neglected by the marketplace, even work that is novel and exciting.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think that ours is the first engineering discipline that’s had to go through this process. You only have to look at the automobile-triumphalist designs of Corbusier to understand how easily the early returns to an invention can be incorrectly projected into the future (in many such cases we should be happy to have gotten away with disappointment rather than outright disaster). Similarly crazed optimism affected observers looking forward to a future full of steel, supersonic flight, radiography and who knows how many other unhelpfully applied technologies.

Now, I shouldn’t overstate all of this; I don’t want to claim that Progress Is Over just because people at SXSW are self-congratulatory dopes. So two caveats. First, it would be a mistake to think that diminishing returns to digital technology means social progress in this realm must be stagnating. Marginal utility declines, but computational power ascends. Individuals are able to perceive the slope of either of these functions and use it to fuel their sense of utopianism or malaise. But to know whether society as a whole is slowing down would require combining the two, which would require more fully characterizing them, and only particularly learned econometricians are wise or foolish enough to attempt that sort of thing.

Second, I dropped the phrase “for a given technological milieu” a couple of paragraphs back, but I’m asking it to do a lot of work. It seems likely that there are thresholds to technological progress at which discontinuities occur — emergence, they call it. Adoption of smartphones, for instance, seems to have mostly been a question of a better kind of telephone/PIM getting cheaper and cheaper, but once everyone has a network node with a flexible UI on them at all times, it seems likely that huge social benefits will emerge that weren’t a consideration in the initial consumer-adoption calculus. But more on this in another post (one that will probably have the word “innovation” in it an embarrassing number of times).

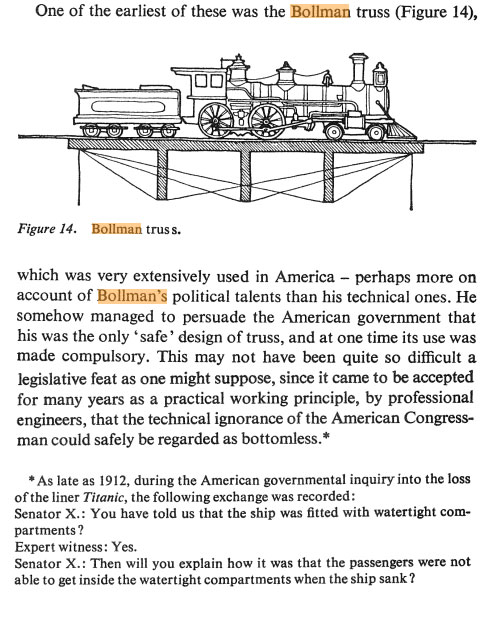

To retreat to my point: I think that in IT, especially, we have a tendency to get confused about whether we’re building a locomotive or inventing the steam engine. It’s a willful confusion, it’s driven by vanity, and it’s now leading to disappointment — and will do so all the more as we find we have enough locomotives on hand.